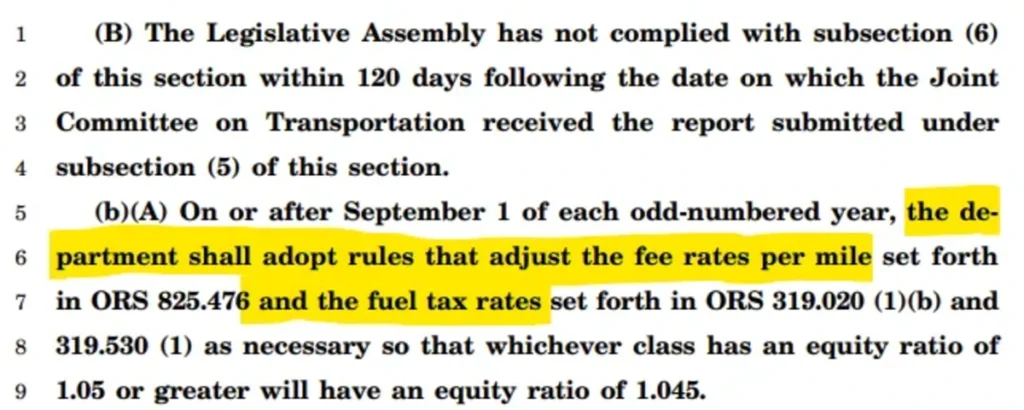

The fate of Governor Tina Kotek’s centerpiece $5.7 billion transportation tax and fee hike bill may rest on a constitutionally dubious provision of the bill that requires the Department of Administrative Services to increase fuel tax rates beginning in 2030, without a vote of the legislature, if it concludes commercial truckers are paying more than their fair share for highway maintenance.

Yesterday, I wrote about the existence of the provision, its centrality in obtaining support for the bill from the Oregon Truckers Association and thus, perhaps, the votes of OTA-aligned Republican legislators. I touched briefly upon the question of whether the provision is constitutional:

The bill would delegate the legislature’s supermajority tax hiking authority to DAS. Article IV, Section 1 of the Oregon Constitution provides, “The legislative power of the state, except for the initiative and referendum powers reserved to the people, is vested in the Legislative Assembly.” The legislature may be constitutionally prohibited from delegating its tax-hiking authority to DAS.

After doing some research and thinking on the topic, I do think there’s a significant risk a court could rule the legislature unconstitutionally delegated its tax-rate-setting authority to DAS in the bill. Such a ruling would prevent DAS from increasing fuel taxes to bring the share of maintenance costs paid by private vehicle drivers, which pay the fuel tax, and commercial truckers, which pay a weight-mile tax instead.

If the legislature were to pass the transportation tax package and a court later struck down the DAS fuel tax adjustment, truckers wouldn’t obtain their long-sought maintenance cost equity, but Oregonians would still be paying the increased fuel tax, payroll tax and licensing and registration fee increases in the bill.

Can the legislature constitutionally delegate its fuel tax rate-setting authority to DAS?

The short answer is, I don’t know for sure and probably no one does. In a nutshell, Oregon, like the federal government, is split up into three main categories: (1) the legislature, which writes laws; (2) the executive branch, which enforces the laws written by the legislature; and (3) the judicial branch, which interprets those laws in response to legal challenges. This separation of powers is central to the American system of government, and is designed, in part, to keep lawmaking authority in the hands of the people and their elected representatives.

At times in Oregon’s history, people have filed lawsuits to challenge the legislature’s attempts to delegate its lawmaking authority to agencies in the executive branch. Courts have ruled there are constitutional limits to how much lawmaking authority the legislature can delegate. In summary, courts have held there are three sources of limits on the legislature’s ability to delegate its lawmaking power:

Those provisions are Article IV, section 1(1), which vests the legislative power of the state in the Legislative Assembly;4 Article III, section 1, which provides that “no person charged with official duties” to either the executive or judicial branches of government “shall exercise any of the functions” of the Legislative Assembly; and Article I, section 21, which provides, “[n]or shall any law be passed, the taking effect of which shall be made to depend upon any authority, except as provided in this Constitution. [Citation omitted].”

There is no absolute prohibition on delegation, however.

The legislature may delegate authority to other bodies “to adopt rules that define or implement broad statutory standards.” [Citation omitted] Whether the legislature unconstitutionally delegates its authority in any particular instance, therefore, depends “on the presence or absence of adequate legislative standards and whether the legislative policy has been followed. [Citation omitted].”

Applying those general standards to the transportation tax bill turns up some potential problems. First, the Oregon Constitution firmly vests in the legislature the power to tax and then only under certain circumstances. Namely, three-fiths of legislators must vote to approve a tax increase.

Moreover, the Constitution specifically addresses what the legislature is supposed to do to ensure fairness between truckers and private drivers when it comes to highway maintenance: “The Legislative Assembly shall provide for a biennial review and, if necessary, adjustment, of revenue sources to ensure fairness and proportionality.”

The tax bill constrains DAS’s fuel tax-rate setting to achieve a constitutionally required equitable burden between truckers and private drivers — the agency can’t just raise fuel taxes for any reason. This language might fit the bill into the “adequate legislative standards” exception, or it might not. So far as I can find, no Oregon court has directly addressed the question in the context of taxation, let along fuel taxation.

The bill requires DAS to set fuel and weight mile taxes based on biannual analyses by the agency about the share of maintenance costs born by truckers and private drivers. There have been problems with the analyses.

This spring, a DAS consultant projected truckers would, under current tax rates, overpay their share of maintenance costs by 26%, while private vehicle drivers would underpay by 11%, according to The Oregonian. The Spring 2025 consultant report corrected errors in the previous DAS study, which had found a larger overpayment by truckers and underpayment by private vehicle drivers.

According to The Oregonian,

Officials said the errors occurred because the analysis included some projects that should not have been taken into consideration, such as federally funded transit projects that don’t qualify for state highway funding, and because they treated costs that will be paid over years, due to bonding, as if they would all be paid in a smaller time frame.

If it passes the bill in its current form, the legislature will be entrusting an unelected state agency to set fuel tax rates based upon analyses the state just earlier this year said were inaccurate. A judge faced with a constitutional challenge to the delegation could well determine reliance on such analyses are not “legislative standards” at all.

Finally, put yourself in the position of an Oregon judge who must stand for re-election to keep his or her job. A case comes before you, in, say, 2031, that challenges the constitutionality of the delegation of tax-setting authority to DAS (there are plenty of potential plaintiffs, including fuel dealers, who might be incentivized to file such a challenge). DAS will have implemented a fuel tax increase by administrative rule to bring truckers and private drivers into parity or close to it, and your job is to determine whether to require Oregonians to pay a higher – potentially significantly higher – fuel tax or to allow truckers to continue to pay more than their fair share. I suspect a judge, especially an Oregon judge, is unlikely to side with the truckers.

It is at best unclear how such a case would come out, and legislators aren’t going to know the answer for sure by Friday. No one knows the answer for sure. The legislative counsel who drafted the bill presumably believe the state has a viable argument for the constitutionality of the delegation provision, and it does. But the law is unsettled on this question, and there’s a real risk the truckers and their legislative allies could be left having voted for a big tax hike without the hoped-for trucker tax equity.

The bill is scheduled for hearing at 3 pm today and, likely, a vote in the House as soon as this Friday.

This article originally appeared in the Oregon Roundup.